CAREERS

Marine Artist, John Barber

by John Barber and Melissa Scott Sinclair

When John Barber was seven years old, he was walking along the beach with his family when they stumbled upon an artist, an older gentleman wearing a blue beret, who was painting the scene before him. Using bits and dabs of paint on his small canvas, he was creating a virtual world of a lighthouse and the vast sea beyond. Young John was thunderstruck by the magic the artist was creating and was overcome with the desire to create such beauty himself. Years later, as an art student in college in Virginia, he was introduced to the nearby Chesapeake Bay and was at once attracted to this great inland waterway, with its picturesque harbors, enduring lighthouses, and graceful workboats operated by hearty watermen. “My love for the sea and for the story of the Chesapeake Bay and her people would eventually direct my entire artistic career.”

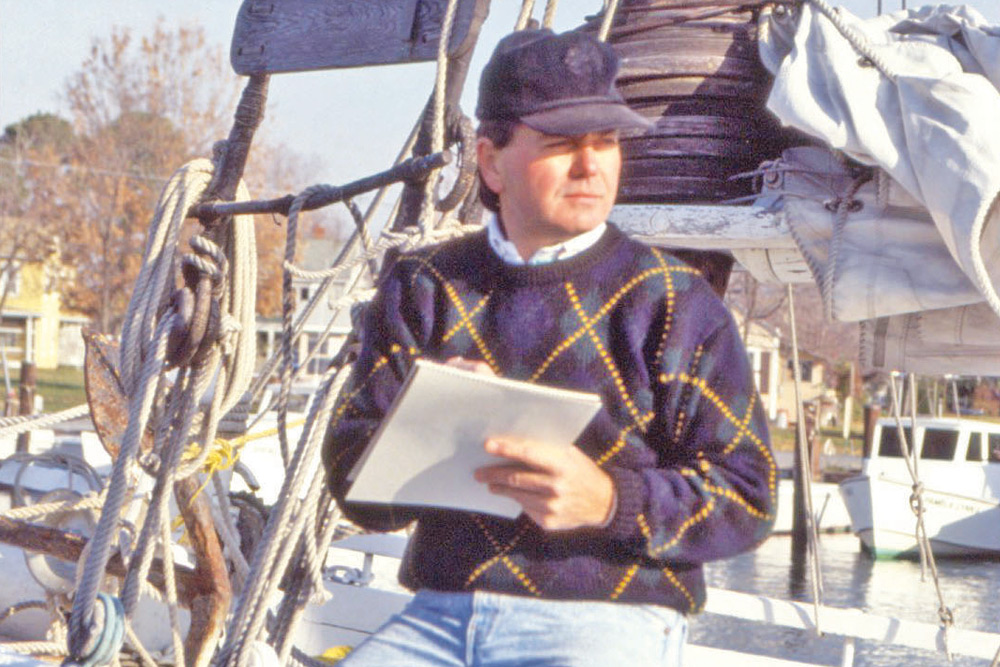

But, it wasn’t enough to paint what he could observe without fully understanding his subjects. “I’ve always been interested in how things work, and so I proceeded to learn as much as I could about my newfound subject.” He built a small wooden sailboat began to explore the waters of the Chesapeake. At first, he would take photos and bring them back to the studio and paint from those images, but soon he started bringing a sketch pad, so he could draw and paint while he was still out in the bay.

Over the years, John befriended the watermen who worked the bay, and with them he sailed aboard most of the surviving Chesapeake Bay Skipjacks. These boats are the last surviving fishing vessels to do their work under sail in North America. Skipjacks are wooden boats designed to sail in the shallow waters of the Chesapeake Bay, dredging for oysters. In addition to skipjacks, John has worked aboard and painted deadrise crab boats, clammers, eelers and gill netters out for a fine catch of fish. When some of these fisheries began to die out, so did these purpose-built boats, but Barber has worked hard to preserve their memory through his artwork.

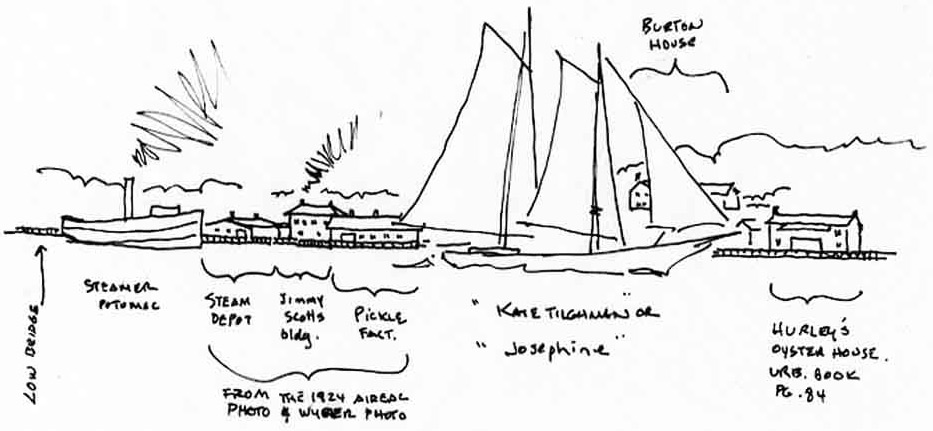

In addition to painting the scenes of today, John has also studied a lot about what the bay might have looked like a hundred years ago or longer. Many of his paintings depict historic scenes, such as his painting (right) of a schooner and a steamboat getting underway from Urbanna, Virginia, in the 1930s.

While John has devoted much of his art to scenes of the Chesapeake Bay, he also recreates scenes of places he visits on vacation. When most travelers would pack a camera, Barber makes sure to pack a sketch easel. Small canvases can be finished quickly within a few hours. Because these are created in nature, or in the “open air,” French impressionists referred to these pieces as “plein air” paintings. Other travelers might keep a scrapbook of their trips, but John Barber has created a collection of art.

John Barber’s art is special, not just for his skill as an artist, but because he has worked hard to understand the history behind his subjects and the intricacies of how things are put together and work. Importantly, he has also worked hard to get to know the people he depicts in his paintings, and this understanding comes through in his art.

Skipjacks at Thomas Point by John Barber

The Subjects of John Barber’s Art

If you look at John Barber paintings, you’ll see all kinds of boats afloat on the Chesapeake Bay. The sailboats with a wide hull and two sails attached to a leaning mast are skipjacks; their job is catching oysters. The big boats with smoke stacks, some with paddlewheels on the sides, are steamships, which once carried passengers and goods up and down the bay. And the white wooden boats with a cabin up top and a mast but no sails are buy boats, which used to carry fishermen’s catches and produce to market.

Years ago, these types of boats were common in the Chesapeake Bay, which is a huge estuary (a place where fresh water and seawater mix) in Maryland and Virginia. Today, only a few skipjacks and buy boats are still around, but not a single steamboat. Steam engines were long ago replaced by diesel and gasoline engines. John has sailed on all kinds of boats—big schooners, racing yachts big and small, and his favorites, the skipjacks. Believe it or not, the artist taught himself how to paint these beautiful boats. It takes a lot of research and practice to learn how to paint the rigging, the sails, and get everything exactly right. When he wants to paint a boat that’s not around anymore, he studies old photographs and books to get a feel for what it looked like.

From Concept to Finished Painting

Photos by Dave Masucci

Did You Know?

Today, nearly 42,000 men and women serve on active duty in the US Coast Guard.

The United States Coast Guard is the nation’s oldest maritime service and is really a combination of five different agencies that were brought together to make them run more efficiently—the Revenue Cutter Service, the Lighthouse Service, the Life-Saving Service, the Bureau of Navigation, and the Steamboat Inspection Service.

What do members of the Coast Guard do every day?